Arm and a Leg: Arm's Quest To Extract Their True Value

Cheap If They Can Charge Qualcomm-like Royalties?

Arm's success can be attributed to its innovative architecture, flexible licensing model, and strong ecosystem of partners. This highly flexible licensing model combined with aggressive investments into automotive, IoT, and datacenter have led to Arm’s margins being depressed for a number of years.

Now the screws are tightening, with Arm looking to maintain a sustainable business model by ratcheting up pricing and coming closer to extracting the value that they actually deliver to the market instead of effectively discounting to secure market share growth. Today we will dive into royalty rates across the smartphone industry and how high they can be ratcheted up, scenarios around what happens with Arm’s nuclear option in the Qualcomm lawsuit, datacenter outlook, Arm’s role in the chiplet ecosystem, Arm China, and RISC-V. We will be sharing our framework and model for the firm’s prospects going forward.

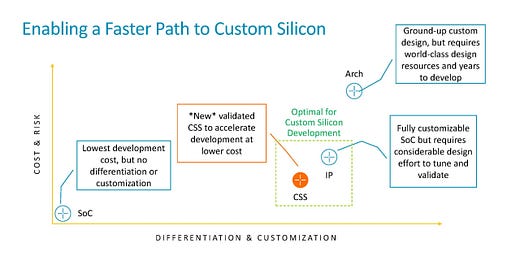

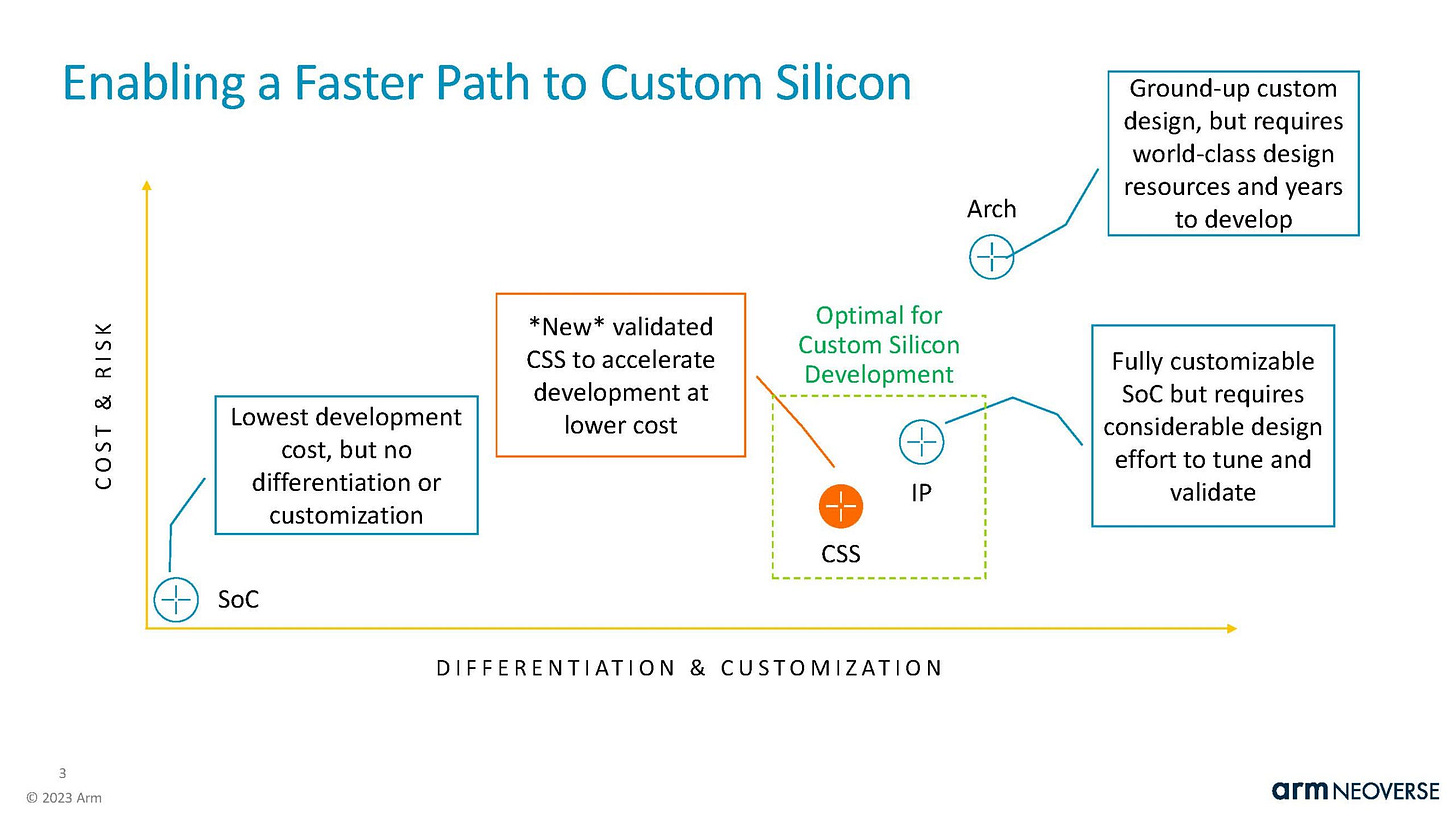

Arm has a range of engagement options with customers and their monetization increases as you go along the curve, from purely their instruction set all the way up to chip design partnerships and chiplets.

Arm is an Instruction Set Architecture (ISA), which is the interface between the software and the hardware, or specifically the microprocessor. The Instruction Set is the library of specific instructions that the chip is able to execute. All code that is written for that particular device is basically an abstraction of a combination of all these instructions. The Arm ISA is the most ubiquitous instruction set in the world, with the other famous one being x86 that we see in many CPUs. RISC-V is also on a meteoric rise.

The Arm ISA moat is very strong, especially in smartphones. We do not see smartphones able to transition to RISC-V anytime soon due to numerous software challenges. Designing a CPU is no easy task, and to date only a handful of firms (AMD, Intel, IBM, Apple, and Arm) have ever designed great CPUs and brought them to market. It requires a lot of time and engineering talent. Money alone doesn’t make a good CPU. Apple licenses the Arm ISA via an Architectural License Agreement (ALA) and has been building their own core for many years. HiSilicon also licensing the Armv9 architecture but with a custom core design was another shocking part of new Huawei’s Kirin 9000S news.

Due to the difficulty in designing custom cores and CPUs, even with the benefit of Arm’s instruction set, most users choose to go with using external CPUs. Those handful of other companies that design CPUs only let you access them if you purchase their chips or devices, whereas Arm’s flexible business model lets you integrate the CPU into your own chip by entering into a Technology License Agreements (TLAs) to purchase “off-the-shelf” CPU designs from Arm.

The TLA can be various degrees of customization of reference designs obtained through TLAs. Customers such as MediaTek use Arm Cortex cores in their smartphone SoCs that are fully off the shelf, whereas Qualcomm’s Snapdragon SoCs have CPU cores (Kryo) that are Cortex cores with some slight customization. All else being equal, TLAs are more expensive with higher royalty rates than ALAs as TLAs offer greater value add and relieve the chip design companies of significant design work.

Arm is also trying to provide more versatile options to suit different customer use cases, for example its recent announcement at Hot Chips 2023 of the compute subsystem (CSS) offering for its Neoverse line of CPU cores for datacenter and cloud computing. The CSS offering is a fully validated block that allows for some customization in terms of memory, I/O and any additional accelerators needed either on or off die. This offers lower cost and faster design cycle time while still allowing for some customization.

Arm is also branching out into more segments, including the contract chip business. This would bring them into competition with Broadcom, Marvell, and more. Instead of just collecting royalties, designing the whole chip would allow them to charge higher prices. This opportunity would also create new customers. For example, phone vendors like Xiaomi or Vivo are designing custom chips with Arm. This would cut out the middleman of Qualcomm and significantly increase the TAM for Arm. Their vast array of IP gives customers many options and their interoperability makes the cost of development lower and time to market shorter. It also enables many new IoT, Edge, and Datacenter players to be stood up.

Whereas other companies tend to grow by upselling products and services to their customers, Arm falls into the conundrum of experiencing an opposite pattern with their customers. As their main customers grow and become more sophisticated, the customers may actually require less from Arm as they start designing their own cores and downgrade from TLAs to bare ALAs.

For example, Qualcomm has been a purchaser of fully off the shelf cores. However, after acquiring datacenter CPU startup Nuvia who are designing fully custom Arm-based Phoenix cores, Qualcomm expressed their intention to use Phoenix Cores in their Snapdragon APs in the future. No doubt, this is part of the dispute between Qualcomm and Arm as this would be a way for Qualcomm to basically sidestep paying Arm for technology.

The compute subsystems are also a way for Arm to absorb more design effort from customers. By offering the compute subsystem as a whole, switching to in-house architecture is more difficult because a whole host of verification, validation, and NOC IP must be brought up.

Arm is even potentially going to offer datacenter CPU chiplets for their major datacenter customers such as Marvell, Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Meta. These firms are designing a variety of chips, from CPUs to ASICs, but that doesn’t preclude them from utilizing an Arm based chiplet that is sold to them from Arm. This would dramatically reduce design costs, which is important as design costs are soaring.

Arm’s Portfolio (Cortex, Mali, etc.)

Arm is featured in a wide variety of chips and devices. The devices that Arm’s architecture and cores power run the gamut of simple micro-controllers, to virtually all global smartphone application processors, up to devices for HPC use cases such as the Nvidia Grace Hopper super chip.

For off-the-shelf cores, Arm’s main product is the Cortex line of CPU cores. Arm also designs GPUs, NPUs, ISPs, interconnects and more.

A relatively recent initiative for Arm has been designing cores tailored for datacenters and the cloud. The Neoverse cores were first introduced in 2019 and they have seen adoption within hyperscalers, featuring in AWS Graviton and Nvidia Grace to name a few examples.

Arm’s Growth Opportunities (or lack thereof)

Like many others, we initially came back underwhelmed after reading the IPO filing. Arm provides truly foundational semiconductor technology and Arm’s IP is shipped in around 30 billion ICs annually. In some applications like smartphones, Arm is the only game in town.

If you were to ask chip analysts what the most important semiconductor companies in the world are, most would include TSMC, Samsung, ASML, Intel, and Arm in their answer. Yet Arm makes a fraction of the revenues of those companies, only earning $2.7B of revenue and about $670M of operating profit at a 25% margin in the fiscal year ending March 2023. Those are good operating margins, but not for a leading semiconductor IP company with dominating market share in its key segments.

Revenue growth at Arm has been decent but far from incredible, Arm’s revenues have grown at a 12% CAGR over the last 10 years. Going forward, Arm’s main end-market smartphones is likely to be a mature and saturated segment. Competition from RISC-V is emerging in low-end microcontrollers. Cloud and datacenter is the most promising segment for Arm going forward in terms of penetration potential, but this segment alone won’t take Arm’s total designed-in shipment volumes much higher.

Taking this into context, the mooted $54.5B IPO valuation would only make sense if there has been a massive change in Arm’s business model, which is exactly what is happening. If you recall back to last year, we were the first to report this change.

This change was to go from charging the chip manufacturer to charging the handset maker too.

We will first discuss the short-term rationale for conducting the IPO before turning to the potential for long-term self-help now that Arm is in focus again for Softbank.

Near Term Rationale for the IPO

A key external factor driving these changes and the IPO transaction itself is to boost the fortunes of Softbank’s Vision Fund and Softbank Group Corp which have been struggling. Softbank Vision Fund 1 is up $12.4B inception to date on $90B of investments, a sub-optimal return for a 6-year-old fund, while Softbank Vision Fund 2 is down $18.6B inception to date.

In 2017, Softbank sold 25% of Arm to Vision Fund 1 for $8.2B only to buy back this same stake for $16.1B in August 2023, on the eve of the IPO. Thus, 65% of Vision Fund 1’s inception to-date gains are from Softbank Group effectively cashing out Vision Fund 1 at a $64.4B USD valuation for Arm in anticipation of the IPO. This transfer valuation is 2x Softbank’s purchase price for Arm back in 2016 and is not far off from the $50B+ likely pricing valuation and the low potential free float of 8-9% could also push Arm’s market cap above $60B post-listing. Therefore, the $64.4B valuation doesn’t appear to be egregiously off-market, though we could say that Softbank Group is doing Vision Fund 1 a solid by allowing the fund to lock in those potential gains before the IPO, albeit via instalments paid by Softbank Group over a two-year period.

The IPO, should it perform well, could also generate significant NAV gains for Softbank Group given it carries Arm at approximately $50B on its books. The listing will also meaningfully boost the proportion of Softbank’s NAV that are held in listed shares, an important prerequisite for boosting Softbank’s flagging credit ratings.

One attempt was to sell Arm to Nvidia but after that failed due to antitrust concerns, Softbank installed completely new management. Long-running CEO Simon Segars was replaced by Rene Haas. In addition, other C-Suite execs left including former CTO Dipesh Patel. It seems there is a desire for Arm to change its mindset of long-term technology investment to profit maximization.

Long-term self-help: How much value will Arm claw back?

Arm powers a whole multitude of chips for various end applications, and the nature of the Arm ISA means it is well-suited to certain applications. Arm has a total monopoly for instruction sets for smartphone application processors. There is simply no alternative as they have almost 100% market share. Our analysis suggests that Arm only makes about 50 cents per application processor on the >1B smartphones shipped per year. This seems awfully low for a foundational part of every smartphone with no viable alternative for chip designers to turn to.

Arm knows this and is now making these changes.

Management has been telling prospective institutional investors that revenue growth will accelerate with mid-20s growth for the next fiscal year and teens growth going forward. The key driver is price. Arm will start aggressively raising the prices it is charging customers. We’ve already seen Arm become less customer friendly given their strategy of maximizing value from Arm’s recent litigation against one of their major customers Qualcomm. This is the bull case for Arm.

How would we value an essential piece of IP that every smartphone needs, with virtually no alternative? $1, $2, maybe $3 per handset? We propose it could be as much as $13 per phone. This is 24 times higher compared to current pricing!

This sounds like a huge amount when anchoring to the current royalty amount per unit, but there is justification and the end customer appetite to pay.

Let’s look to Qualcomm as an example. Any device that uses 4G or 5G will use multiple technologies that Qualcomm owns the IP for. One example is Qualcomm owns the Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA) and Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiple Access (OFDMA) technologies for wireless communication. 3G networks worldwide are exclusively based on CDMA and 4G and 5G networks use OFDMA as the communication protocol.

In short, CDMA and OFDMA are essential for transmitting data wirelessly beyond the 2G era of wireless communications and thus every smartphone vendor pays Qualcomm a royalty for the use of these and other essential wireless technologies to enable wireless communication. On top of these royalty payments, there is also a good chance any given mobile handset manufacturer is also paying Qualcomm to use its baseband chipset as Qualcomm has over 30% market share in smartphone basebands (and over 60% in 5G basebands).

Using a concrete example, Apple pays Qualcomm $13 in royalties per device (not just for smartphones but also for wireless enabled iPads and watches) for the use of wireless transmission IP, and another $25 for the actual baseband chip.

Effectively, $13 per device this is what Qualcomm gets away with charging for a technology that is essential to the operation of a smartphone against the company with arguably the strongest bargaining power globally.

The Arm ISA is also essential to the operation of a smartphone, why couldn’t they charge as much as Qualcomm? Why not more?

Another interesting point to mention is that Qualcomm’s pricing model is based on a percentage of the BOM cost or selling price of the whole device that uses Qualcomm’s IP, not just for the components using the IP directly. So, when a systems customer adds more expensive features that are completely unrelated to wireless communication – say for instance higher NAND storage capacity - Qualcomm gets to capture some of this value. No wonder Qualcomm is disliked by its customers, especially by Apple who constantly try (and fail) to litigate their way out of paying Qualcomm so much.

Clearly, Arm sees the similarity with their own and Qualcomm’s market position, which is why Arm is starting to adopt a similar pricing strategy. Ironically, Qualcomm is one such large customer who is kicking up a fuss about Arm’s new pricing strategy. At the end of the day, we think Arm’s dominant position gives it the flex to execute on all the various strategies that can boost revenue per smartphone shipped, assuming Arm actually wins in the nuclear option.

What this could mean for Arm’s financials

Let’s see what the impact would be to Arm’s financials. We will take a conservative stance in assuming that per device revenue increases only apply to non-Apple smartphones given that Apple has secured terms for architecture licenses for the next 2 decades and will always enjoy a sweetheart deal due to their long term history in founding the firm.

We segment smartphone shipments into the high-end, mid-end and low-end units excluding Apple. Assuming $12, $6, $3 of royalties per unit for each segment respectively, incremental revenue and profits (there will be zero incremental expenses) results in an additional $5.4B of operating profit for Arm which would almost 10x Arm’s operating income!

This sounds ridiculous when anchoring to Arm’s current pricing strategy. But if we go back and try to answer the question: “what is Arm’s IP worth to a customer?”, from first principles we don’t think there is a significant counter argument to easily dismiss this line of reasoning.

Of course, this is an optimistic scenario, and it would take a lot of time to get there. Customers will try to fight back. Currently Arm will not be able to raise rates on Qualcomm as long as they are able to integrate their custom core over the next couple years and the lawsuit fails. But this should provide a sense of what investors are playing for and that the ceiling for Arm’s profitability is much higher than where it is now. We can now see the valuation start to make sense instead of focusing on the historical earnings power and growth rates or earnings forecasts for the next year or two.

Next we will discuss RISC-V, x86, Hyperscaler Arm adoption, Arm China, and our model for the financials as well as comps. We are only halfway through so far.