Fab Whack-A-Mole: Chinese Companies are Evading U.S. Sanctions

Huawei Fab Network, WFE Vendors Cry Wolf, Framework for Future Controls

AI competitiveness is a key national security concern. When “expert-level science and engineering” or even AGI are possible outcomes, it is crucial that the U.S. maintains or extends its lead in these areas. Consider the opposite: what if China were to achieve AGI capability six months or a year before the U.S.?

There are a few major gating factors to building powerful AI systems, and the only one the U.S. can stop from proliferation is compute. Currently the largest AI training clusters are ~100,000 GPUs. Over the next few years the growth of the largest AI clusters is primarily capped by U.S. regulatory environment and industrial capacity limitations. As such, all major US AI firms are turning to the unproven method of scaling AI by training models across datacenters around the nation.

China on the other hand has no issues securing power infrastructure or datacenter capacity. There are numerous multi-gigawatt substations that can be converted from aluminum mills to datacenters in less than 6 months with minimal impact to national production. Datacenters are not a limitation like they are in the US. This means China could leapfrog American firms in total compute while also not dealing with various potential drawbacks from cross-nation training runs.

While the conventional wisdom is that China cannot build AI supercomputers due to chips limitations, this isn’t true. There are enough chips being shipped to China + manufactured domestically to create the world’s largest AI training cluster. For the most part, AI chips are decentralized in China with the largest known clusters 1/3 the size of the largest US ones, but a concentration of efforts could lead to cluster sizes that dwarf those in the US in less than a year.

While the US is trying to prevent this through export controls on advanced technologies throughout the AI supply chain from chips to wafer fabrication equipment. A cat-and-mouse dynamic between U.S. regulators and the Chinese domestic chip supply chain has ensued: in general, the regulations capture the low-hanging fruit which has slowed Chinese progress. China has significantly fewer H100’s then they would like, but they are still available in relevant quantities from multiple clouds and marketplaces in China due reexportation by various bad actors.

But the U.S. also left loopholes that are routinely exploited. For example, Huawei has been able to scoot around TSMC’s weak end customer checks and secure thousands of leading edge wafers through Bitmain / Sophgo, and many other established Chinese design firms. While this is a huge failure in enforcement of the export controls, it’s also relatively low volume compared to domestic fabrication of the Ascend 910B. Huawei has been relying on primarily SMIC to produce their domestic AI chip and they have run tens of thousands of wafers of the main compute chiplet on their domestic SMIC N+2 (~7nm) and N+3 (~6nm) process nodes.

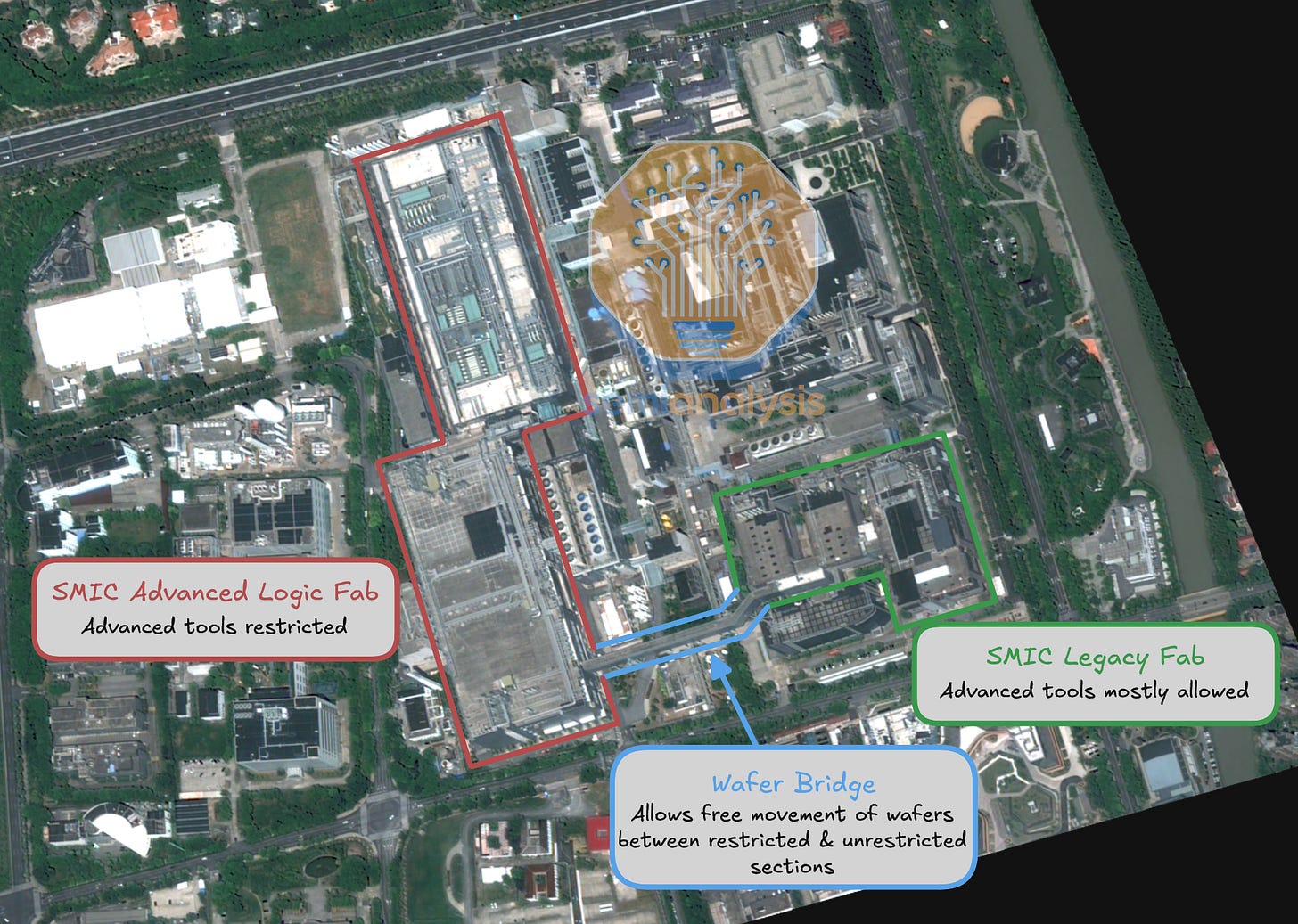

Sanctions violations are egregious. SMIC produces 7nm-class chips including the Kirin 9000S mobile SoC and Ascend 910B AI accelerator. Two of their fabs are connected via wafer bridge, such that an automated overhead track can move wafers between them. For production purposes, this forms a continuous cleanroom and effectively one fab.

But for regulatory purposes, they are separate! One building is entity-listed by the U.S. and working on advanced logic for AI chips, a clear national security concern. The other is free to import “dual use” tools as it runs only “legacy processes.” Do you believe they aren’t sharing anything over the wafer bridge?

In addition to utilizing SMIC, Huawei is also aggressively snapping up their equipment for its new fab network. This is a sanctions-evading scheme, closely supported by the Chinese state. The goal is to build out domestic capacity at every step in the AI supply chain including leading edge logic, memory, advanced packaging, and optics.

The scale and speed are staggering: we estimate the Huawei fab network will spend $7.3B on foreign wafer fabrication equipment in 2024, making it the 4th largest purchaser in the world. If SMIC and CXMT are included, both of which work closely with Huawei, they would be the 2nd largest purchaser in the world only behind TSMC, and far ahead of any US firm. More than half of this equipment currently comes from US companies.

This begs the question of what export controls should look like going forward. It’s clear the entity list approach is easily circumvented, but we believe it is fixable. There’s the option of invoking the toughest version of the Foreign Direct Product Rule, meaning the U.S. could exert control over equipment containing any American content, rather than the >25% set by the current de minimis guideline. Lobbying efforts from equipment companies suggest that restrictions should be relaxed or totally repealed because of harm to their business, but this is far overblown. Relaxing the controls would be a serious unforced error that would harm American suppliers and U.S. national security in the long-term.

In this report we’ll discuss all these issues, laid out under 4 key points:

Existing controls are effective but need continued updates and stronger enforcement.

The nascent Huawei fab network is a key concern. It is a state-backed, rapidly expanding entity that actively circumvents U.S. export controls to grow Chinese advanced semiconductor capabilities.

The Economic effect of sanctions on U.S. WFE suppliers are exaggerated. There is clear evidence after two years under the controls that the companies are not suffering, they are thriving.

Sanctions and enforcement must be improved in the face of rampant evasion by Chinese firms and easy workarounds available to Western tool suppliers.

We’ll outline the options and what should be done going forward.

For further background, we’ve covered this topic in depth from the start: 1st round of controls in 2022, SMIC ships 7nm ASICs anyways, Biren evades restrictions on its AI chips, many gaps were left even in the lithography controls, sanctions have not stopped progress, and round 2 of controls in 2023.

Existing Controls

Current Western export controls have slowed progress in China. The current gap in advanced logic is approximately 5 years, with SMIC’s N+2 process shipping in 2023 versus TSMC’s N5 in 2020 and N7 in 2018. Parametric yields on advanced SoCs and especially large-die HPC chips are rumored to be poor. Without government subsidies these logic fabs would not be economically viable, but generally the scale of subsidies required are tiny relative to the subsidies China has historically given other industries such as EVs, steel, and solar. The Chinese government’s increased emphasis on developing domestic alternatives is also a strong indication of strategic effects.

But this does not mean the regulations are perfect or will work ad infinitum without updates. We’ve covered the technology gaps in multiple reports, but there are also loopholes in the practical implementation of current restrictions:

Offshore Manufacturing

Western companies now offshore supply chains to export U.S. technology into China. An isotropic etch chamber, essential to producing the latest 2nm Gate-All-Around transistors, cannot be exported to China from Lam’s U.S. factories. This same etch chamber, manufactured in Lam’s Malaysia facility, can legally be sold to an advanced logic fab in China if no U.S. persons are involved (in manufacturing, sales, installation, and servicing). This includes even customers on the U.S. entity list. Other companies follow the same playbook, including Applied Materials & KLA with their Singapore facilities. Equipment component companies such as UCTT are also doing the same. And why not? Any rational company would do the same to further their business under the current restrictions.

End-Use Workarounds

Narrowly tailored end-use restrictions, intended to limit collateral damage to non-military or non-strategic applications, open a loophole that is easily exploited. A logic fab claiming to produce mature logic can import leading-edge tools (except for those on the current control list, which limits a small number of exquisite tools such as EUV scanners) despite being connected by a wafer bridge to one running advanced nodes next door. With an automated overhead track connecting the two, advanced tools in the mature fab are easily available to the restricted logic line. Even easier, tools can be delivered to a warehouse and later moved into any fab, restricted or not. Flimsy public compliance statements provide legal cover while installs continue unabated.

Tools imported for mature processes can easily be used for restricted purposes i.e. advanced logic or memory.

Rename & Reclassify

CXMT’s advanced DRAM with 18nm half pitch was subject to the original 2022 export controls. A new method of calculating half-pitch in the 2023 rules put them back above the minimum line for controls. Without changing the underlying process, they went from restricted to not. They also changed the node name from 17nm or 18.5nm to 19nm, to avoid any appearance of impropriety. The subtleties of the rule change that so specifically moved them from under to a literal nanometer or two over the restriction are, at least, very fortunate for CXMT. Lobbying efforts by giants such as Applied Materials who has made over $3 billion from CXMT may be noteworthy.

Huawei Fab Network

Of all sanctions-evading schemes, Huawei’s fab network is the most alarming. It is a clear national security concern as Huawei is CCP-affiliated and a leader in Chinese AI. In response to U.S. restrictions, Huawei embarked on a massive government-sponsored development project to build out a domestic semiconductor supply chain. Between acquisitions and startups, Huawei now controls firms across wafer fabrication materials, equipment, optics, chip manufacturing (specialty, memory, and advanced logic), and chip design. They span the entire AI and mobile ecosystem with these efforts.

This was reported by Nikkei Asia, last year by Bloomberg, and more recently in a letter to the Secretary of Commerce from the U.S. House Select Committee on the CCP. But it hasn’t received enough attention.

Looking at the incomplete corporate family tree, there is a clear gap in the U.S. Entity List. Many fabs and entities upstream in the supply chain are not entity listed, despite being controlled by Huawei which is. The non-listed companies are free to import advanced equipment while claiming not to share it with their restricted peers. This gap is exploited by Huawei.

They are following the SMIC playbook: Pengjin High-Tech, a GaN startup that is not entity-listed, is building its cleanroom across the street from entity-listed advanced logic producer PXW. Pengjin is free to import nearly all advanced Western production equipment, including equipment critical to producing advanced logic at 7nm or below (again the exceptions are a small number of tools on the control list, including EUV). Yet again regulators are expected to believe that nothing will be shared with its neighbor.

And this happens over and over. Take the example of a new Shenzhen Pensun fab is located next to SMIC. Recall that SMIC is the advanced logic leader, at least for commercially available processes, in China. One is entity listed, the other not:

In the race between shell entities and regulations, shells can be spun up faster than regulations are being updated. Huawei is clearly taking full advantage to the tune of $7.3B of WFE expenditure in 2024, up 27% year-on-year. They’ve gone from effectively zero in 2022 to the 4th largest WFE customer globally in two years. If we add SMIC and CXMT, both of which are affiliated with Huawei, they become the 2nd largest customer globally.

Bear in mind this is a state sponsored company not a free-market competitor. Huawei is closely affiliated with the Chinese state to the tune of $30B in funding last year. They are evading sanctions and advancing the domestic semiconductor supply chain, producing chips intended for AI and military end-use.

In some cases, Huawei is even developing significantly more advanced chips then western firms for example with their affiliate Swaysure who has a capacitorless 3D DRAM that breaks through The Memory Wall barrier. The memory wall is currently a big impediment to AI hardware and model progress.

Effects on WFE Suppliers

Despite rampant abuse of the restrictions and a clear national security concern, fab equipment suppliers are pushing for relaxed controls. Extensive lobbying operations spread fear, uncertainty, and doubt (“FUD”). Their argument centers on present and future harm to the business, mostly due to fears that restrictions will result in foreign competitors taking market share.

In a letter to the Department of Commerce earlier this year, Representative Lofgren and Senator Padilla from California say that “some companies are even at risk of a ‘death spiral.’”

This is absurd and easily refuted:

Two years of data since the initial export controls, shown below, falsify this narrative. There is no existential risk or serious harm to Western suppliers’ business due to the restrictions. In fact, it has been among the two of the best years ever for WFE vendors.

Long-term market share will be impacted more by domestic replacement from Chinese firms than regulatory controls. Chinese companies ignore IP restrictions and are heavily government subsidized. This will erode Western companies’ competitiveness in the longer term regardless of any export restrictions.

Here’s company performance data. By nearly every metric the 24 months under export controls have been among the best in history for American WFE suppliers.

The WFE majors outperformed SOX:

Even during a semiconductor downturn, WFE suppliers maintained near all-time high revenues:

Gross margins expanded during this time period, not contracted…

…And the primary reason is China.

Once Chinese firms realized they could skirt the rules, they exploited loopholes to their benefit. Sales exploded in anticipation of gaps being closed in the future.

Sen. Padilla and Rep. Lofgren claim the restrictions are strangling R&D spend. Clearly this is not the case:

Company executives on earnings calls also tell a very different story than that being spread on Capitol Hill (emphasis added):

On further tightening export controls past the original October 2022 ruling:

Our view is that it's not incremental if -- if it weren't allowed to be shipped [to China], that it would be shipped somewhere else in the world for production.

-Brice Hill, CFO Applied Materials, Q3 FY23 Earnings Call

…In 2023, Applied grew faster than the wafer fab equipment market for the fifth year in a row.

We accomplished this despite headwinds created by trade rules that we estimate restricted us from more than 10% of the China market during that period.-Gary Dickerson, CEO Applied Materials, Q2 FY24 Earnings Call

Regarding the 2023 restrictions update which included market segments important for AMAT - epitaxial growth, metal deposition, Cobalt or Copper hardmask, and atomic layer deposition tools:

We do not expect an incremental material impact from the recently updated trade rules. Our business in China grew as expected in Q4 (2023)

-Brice Hill, CFO Applied Materials, Q4 FY23 Earnings Call

Lam recovered within a year when their largest customer was zeroed out via regulation:

…Perhaps our largest customer got restricted when the regulations came out, our NAND customer in China. That customer was pretty strong in '22, went away in '23… the strength we're seeing '23 to '24 is a different mix entirely, really not any NAND in China to speak of, at least not domestic China.

-Douglas Bettinger, CFO Lam Research, Q4 FY24 Earnings Call

More than six months after the 1st round of export controls:

Our market share [in China] continues to be strong. I mean, we started focusing on legacy market opportunities several years ago. In fact, we started some older product lines, and they continue to be the most competitive really at all price points in terms of -- so we feel while there is more competition trailing edge, we're very well positioned to be able to win.

-Rick Wallace, CEO KLA Corp., Q4 FY23 Earnings Call

And for 2025, the semicap majors are all guiding to their best year ever:

Do these sound like companies in a “death spiral”? Obviously not. Despite a short-term shock or loss of business, the slack is taken up by customers ex-China within a few quarters. While the officers of these companies have a duty to push back on restrictions and therefore maximize their business, the narrative of export controls causing undue harm is overblown.

To be clear, the sanctions do impose a cost on American companies. It would be difficult to design them in a way that did not at least cause hiccups or temporary disruptions to business. But the cost here is not existential – it is short term, recoverable, and therefore worth it in service of national security. Especially since ex-China revenue is about to increase with future leading-edge demand.

Another common argument is that if only U.S. companies are further restricted, foreign tools will backfill the market – a lose-lose outcome that removes the American firm from competition while failing to restrict key technologies. We suggest that those easily replaced will, regardless of restrictions, lose share to domestic Chinese firms anyways.

Take the example of a relatively mature technology: etch tools for dielectrics or copper. A ban on U.S. firms Lam Research and Applied Materials would theoretically leave a void to be filled by Japan’s TEL. Realistically this share is likely to be taken by Shanghai-based AMEC no matter what the West restricts. This is the Chinese government’s primary imperative in semiconductor equipment. Market share is governed not by free market competition but by subsidies and compulsion to buy domestic.

More advanced tools tend to have fewer competitive suppliers. For example, only Lam and TEL can product cryo etch tools needed for advanced 3D NAND. A U.S. ban on Lam would of course gift TEL the China market, as currently there is no viable Chinese competitor (note that TEL might take that share anyways on the basis of producing a better tool). Except that TEL cryo etch tools contain US content in design, software, and subcomponents.

In this scenario, a multilateral restriction including the U.S. and allies is desirable. A unilateral U.S. restriction where allies allow the export of competing tools ends with the lose-lose outcome described above. An alternative is lowering the U.S. content threshold to 0%, which would prevent TEL from shipping to China as they use US IP, software, and/or components in every tool they ship.

Generally anything in the medium to hard categories shown below should not be unilaterally restricted when viable foreign competitors exist. This would lead to the lose-lose outcome described above. For technologies towards the easy end of the spectrum, Chinese firms will take market share in the short-term either way. Ideally: let Western companies compete in the easy categories while multilaterally restricting the medium and hard categories.

Note even the easy tools are imported in huge volumes because “easy” in semiconductors is more complicated and harder than most entire industries. Keep in mind that long-term (think years or even decades) all these firms are likely subject to the “China Technology Cycle.” This means Chinese competitors obtaining, copying, and flooding the market with a similar product at lower price. There are many examples including solar, lithium-ion batteries, and soon lagging-edge chips. It will be more difficult with semiconductor equipment but there is no fundamental reason it won’t occur. There are already a few cases: Aixtron’s technology was copied which destroyed their market share.

Selling tools to Chinese fabs now will only expedite this process. In many cases, the domestic Chinese tools are set up right next to the foreign western tool and have the same experiments run on both constantly to get the domestic Chinese tools to utilize data, calibration, and baseline readings from foreign tools.

Future Restrictions

Given that it’s possible to impose controls without serious harm to WFE companies, and that current restrictions have many flaws, let’s turn to how they might be improved.

Starting on a positive note: the export controls are clearly having a strategic effect on Chinese capabilities in advanced memory and logic. We should also give credit where it’s due. The U.S. government correctly recognized the strategic significance of AI before it was obvious and acted on it. Recall that the first round of WFE export controls were released more than a month before ChatGPT and the ensuing transformation of AI.

The current export controls comprise country-wide restrictions on a few exquisite tools and more severe controls on a select sub-set of fabs via the entity list and end-use controls. U.S.-made equipment and foreign tools with > 25% U.S.-origin content are subject to the entity list and end-use controls. U.S. persons are also prohibited from servicing restricted equipment. Despite the WFE vendors lobbying, these are the most important controls in effect today, they are not killing our domestic manufacturers, and they should not be walked back.

Allied governments, most importantly Japan and the Netherlands, have generally aligned their country-wide restrictions with the U.S. But they have not aligned on the entity list or end-use controls, meaning fabs presenting acute national security risks can still receive certain advanced equipment.

And the efficacy of controls is eroding in the face of a massive, organized evasion effort. It’s clear they miss advanced equipment sales to key players, especially Huawei and SMIC.

Lessons from the past two years under export controls must be learned: the fab whack-a-mole approach for entity listing is not effective. It’s trivial to set up a friendly, non-restricted entity next door. Instead fabs in China should be considered fungible. It should be assumed that end-use cannot be controlled once equipment is in country.

One option is lowering the content threshold to 0%. This tightens restrictions such that equipment with any U.S. content will require a license from the U.S. for sale or service to restricted entities. By applying this standard the U.S. could unilaterally prohibit sales of Dutch and Japanese manufacturing equipment relevant for advanced logic and DRAM. At its own discretion the U.S. could stop Chinese capacity expansion immediately, and existing fabs would be severely handicapped if not inoperable within six months.

This would placate U.S. equipment firms as it eliminates any imbalance between U.S. and allied restrictions. It clearly accomplishes the strategic goal of limiting Chinese AI capability. And it leaves little room for circumvention in the short-term.

But the 0% threshold has serious downsides:

High diplomatic cost. Allies will take offense to the U.S. unilaterally restricting their firms, especially the Netherlands which sees ASML as one of its crown jewel companies.

Chinese response will be severe as their short- and medium-term chip production is destroyed.

Strengthens the perverse incentive to remove all U.S. contents, persons, and production from the supply chain. Foreign manufacturers will try to design all U.S. content out of their tools. Note, even in the medium-term this is effectively impossible.

Take for example the Windows operating system – not only would removal require a major overhaul of the software stack but it’s not clear sufficient alternatives even exist.

Removes tool data visibility. All advanced wafer fab equipment reports some level of detailed information back to support organizations at the manufacturer and local field service. China’s national security laws prohibit U.S. companies from sharing this data with foreign parties, so it’s unclear how much value would be lost here.

The 0% threshold is effective but has high cost. If AI is going to transfrom society and the world over the next decade, then it must be applied. The national security risk of not applying it, is too grave.

Improvement is also needed on restrictions upstream in the WFE supply chain. Current sanctions are strict downstream on AI accelerator chips and similar. They are looser upstream on equipment to produce these chips and non-existent for components of that equipment. This strongly incentivizes and enables China to develop an indigenous capability in manufacturing equipment, eventually rendering sanctions toothless. Instead, restrictions should be stricter upstream – tight on equipment and tighter on its key components.

For example, current controls prohibit exports of EUV scanners into China. Yet they do not restrict EUV optics from Zeiss. This makes no sense – ASML and any chipmaker using EUV can tell you that projection optics are the #1 critical component. While it is not practical to control every nut and bolt, certain items obviously must be. Where to draw the line? There are fewer than 100 critical components from specific suppliers that should be restricted, including EUV projection optics, precision mask stages, and radio frequency plasma generators.

Keeping upstream components on-shore also has benefits because of margin stacking. Just a billion in restricted tools means a 2x+ downstream on foundry and even another 2x on fabless revenue going to a Western firm rather than Chinese. In real terms, a $2B trailing edge fab will make $15B+ of chips over its lifetime and that will go into $100B+ of electronics, automobiles, etc. Additionally, the Chinese government through Huawei is subsidizing the entire cost, meaning that the foundry, fabless, and electronic manufacturer has almost no need for margins. The only chokepoint in this scenario really is wafer tools and components, so these must be constrained.

We’ve focused on advanced process technologies here – logic and DRAM. Reason being, when it comes to older processes, the ship has effectively sailed. China has built massive internal capacity for legacy processes. Further controls may not be effective, especially as Chinese domestic equipment is already capable at these nodes. A flood of Chinese legacy chips threatens to run Western competitors out of business.

This is concerning as mature processes are still vital to national security-related applications. Attention and likely intervention are needed to maintain on-shore development and production capacity for legacy nodes going forward. We’ll leave further discussion to a separate report.

Note that we are talking about the goal of sanctions and not the implementation when leaving mature applications out. Given that fabs assisting in advanced processes may also run mature nodes, sanctions with the goal of limiting advanced applications must be implemented in a way that restricts certain “mature” fabs.

In summary:

Pragmatic and effective options exist for improving the export controls. They are not causing undue harm to WFE suppliers nor will these improvements. Restrictions must be tightened.

The entity list must be expanded and updated often in response to sanctions evasion via startups. This means monthly updating, as well as geographic checks. If we can find this with some satellite photos in trivial time, it is clear the rules are easy to skirt. The Huawei fab network should be restricted, the 0% threshold should be considered for their inbound equipment.

Allies must match the restrictions on both equipment and servicing. The stakes are not next quarter but the next decade: an AI-capable China does not serve their national security interests. Domestic firms will also suffer long-term. Exporting advanced tools provides immediate gains but hastens replacement by Chinese competitors.

Restrictions must be tighter up the supply chain. WFE tighter than chips, critical WFE components tighter than WFE.

Enforcement must be improved with the presumption that equipment imports are for restricted purposes until proven otherwise. End-use checks should also be repeated regularly, not just on install. It is trivial to change applications after the fact.